To what extent should new buildings in Chester make reference to the incredible architectural legacy of the place? Should future buildings be black & white? Or perhaps, they should be faced with red brick and include a blue diamond pattern? Should they be Georgian in style? What about half-timbered? Maybe they should at least include an historical motif from an earlier building?

How can a new building add to the wealth of character that already exists in Chester? Should new buildings pay homage to the past, or be neutral and unassuming? Or perhaps they should boldly forge a new path that adds to Chester’s diverse architecture?

These difficult questions have been faced by many an architect when trying to tackle the problem of how to design a new building in an historic town.

We all know that appearances are only part of the story. New buildings need to contain the right uses and be of the right size and scale as well as fit in with the existing pattern of development and public spaces. However, even when all of these things have been addressed, the issue of what the building looks like remains vitally important.

I am privileged to have been a member of a number of design review panels around the UK, including in Chester, where I have witnessed other architects dealing with these issues. There is something compelling about a place of great character which causes architects to want to reflect that character in their designs. Whilst this approach can be well intentioned, it can be construed as patronising when the developer thinks that giving the locals, or the planners, ‘what they want’ will make it easier to obtain permission. What makes them think they know what other people want?

So how else could the problem be approached? Well, one way is to do something completely different and there are two buildings in Chester that I refer to when providing antidotes to the 'designed to reflect the place' approach: The town hall and the Odeon.

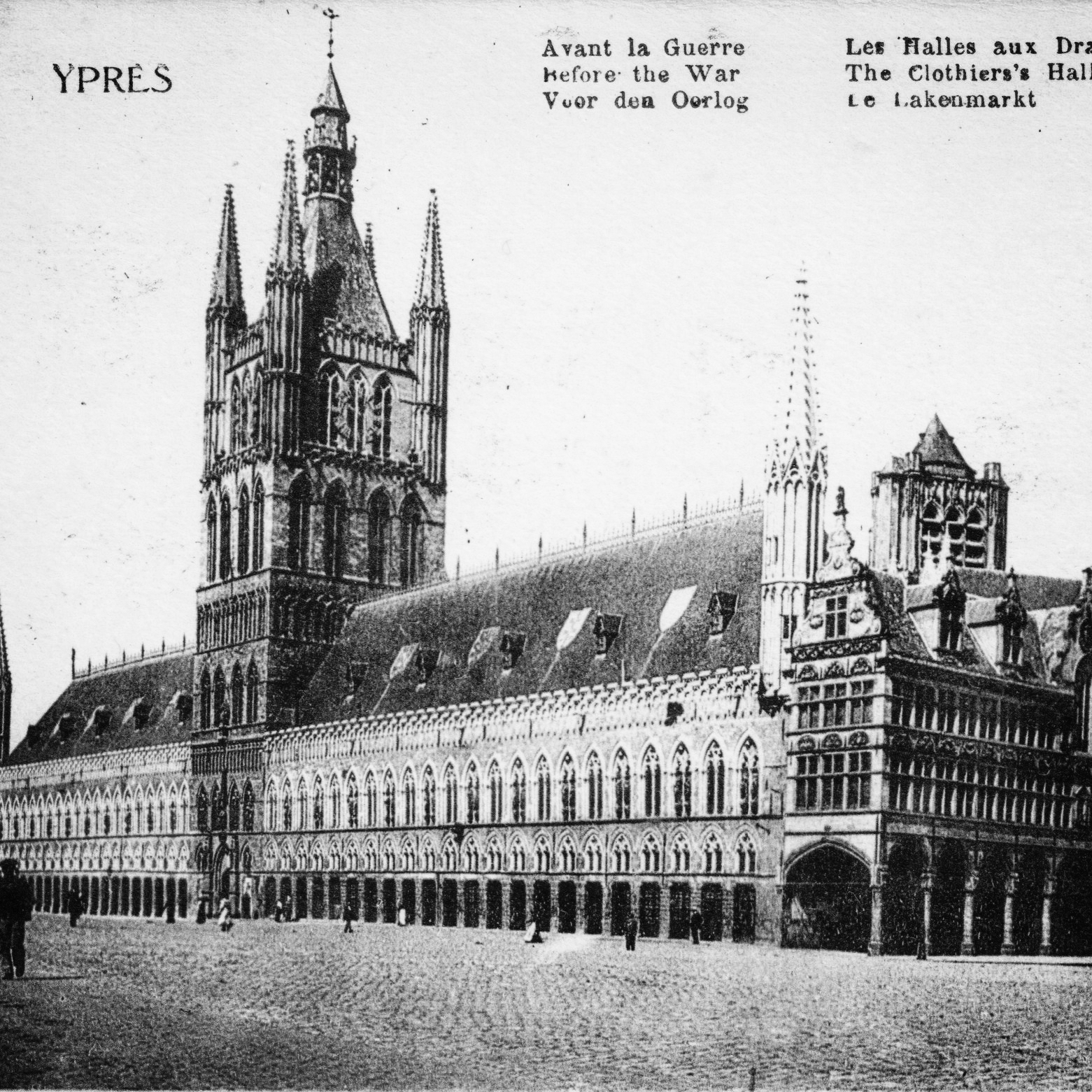

Following the destruction of the previous administrative building by fire, the design of the current Victorian town hall emerged from a design competition which was won by an architect from Belfast. The architect took his inspiration from a building known as the Cloth Hall in Ypres, Belgium. And as such, he then set about designing the town hall in a neo-gothic style, a style which had some, but not much, track-record in Chester. Other than the use of local sandstone, the town Hall has no external reference to earlier buildings in the city.

In the 1930’s the Odeon company were rolling out their cinemas across the country. In all towns and cities Odeon buildings were designed in the art-deco style and faced in ceramic tiles. All except two that is. In Chester and in York, the local councils objected to the use of ceramic and insisted on a more restrained design in brick. The Odeon's designers obliged with 1930’s art-deco style buildings faced in brick. However, these buildings made no overt reference to the rich history of brick construction in either place.

What is it that links this Victorian neo-gothic building with this 1930's Art Deco building, other than the avoidance of references to earlier buildings?

In my view, the answer is design quality.

When the design quality of a building is sufficiently high there is no need to pay homage or make references to earlier buildings in the city. Quality buildings stand up for themselves and don’t need help from the supporting cast around them.

Of course this issue of referencing the place exists at one level for an individual building but is much more of a problem when considering large-scale comprehensive redevelopment. When a single developer and a single designer tackle an entire city quarter, the temptation to reference the earlier buildings becomes even stronger. It is often the case that as the size of the development increases, there is a proportional decrease in the 'design energy per square metre’ (to coin my own new term). This results in an increased desire to raid the heritage of the place in an attempt to compensate for the shortcomings of the design.

Chester, along with most other historic cities, does not have a particularly good record of comprehensive redevelopment in terms of design quality. It is almost as though the two things, heritage and large-scale development, are mutually exclusive. However, I don’t think they have to be, what is needed is a new way of thinking about our models for development.

We need thinking that recognises a masterplan for what it should be, a plan for future development, by others, over time. Thinking that allows the re-sale of land so that the ownership and authorship is diversified; that allows new and innovative city centre uses to flourish in our digital and ageing times; that allows the 'design energy per square metre' to be maximised; and that allows local distinctiveness to bloom. If in doing this, the design quality of buildings is improved, the temptation to reflect the place in future buildings will diminish and we will see fewer black and white facades, red brick gables or historical motifs, however abstracted these may be.

An example of this new way of thinking is the recent opening of Storyhouse, which places Chester in the vanguard of those cities committing scarce public funds to major public buildings. In the era following the UK's Millennium Projects, several of which failed, a more sophisticated approach was required to the development of large cultural buildings. The solution has been to find ways of growing the audience far in advance of the construction of the building. In this way the risk of failure is greatly reduced when compared to a ‘build it and they will come’ approach and the sustainability of the building is much more secure. The local authority in Chester deserves credit for such a forward thinking approach.

Chester's future should certainly respect its historical legacy, but this need not be literally reflected in the appearance of its new buildings. There are huge opportunities for innovation in the centre of Chester. The way in which new development is carried out and the quality of the resulting buildings ought to build on the groundbreaking work at Storyhouse. In the 1960’s Chester led the way amongst the country’s heritage cities. It longs to do so again, and could. But, this will require that we take more risks, think differently and act boldly.

This post was written for Issue #2 of Tortoise magazine. The published article included illustrations by Laura Knight not shown here.